Hormuzd Rassam was an extraordinary person. Traces of his unique relationship with Magdalen can be found in the archives and his generous donations to the College became a lasting legacy. Yet, his pioneering archaeological work was persistently overlooked during his lifetime and for much of the following century.

Hormuzd Rassam was born in 1826 in Mosul, a diverse and beautiful city in Ottoman Mesopotamia, now northern Iraq. From 1846, Rassam was employed by Austen Henry Layard. Layard was an English gentleman archaeologist who had travelled to Mosul, where Rassam’s brother was Vice-Consul. Hormuzd Rassam’s crucial task was to liaise with local officials and employees, who were essential to the archaeological excavation of the ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud, including the palace of King Ashurnasirpal II dating from 883–859 BC.

From 1847, Rassam spent over a year studying informally at Magdalen. Layard sought a college for his assistant and friend that would offer ‘a good English education… & most important of all the inculcation of English principles & feelings’.[1] Rassam studied with a theology tutor and enjoyed a warm social relationship with the President and his wife.

Hormuzd Rassam was unique. We have found no evidence of other students of colour studying at Magdalen before 1920 and, indeed, even Rassam was never formally admitted to study here. Do the archives allow us to understand how it felt to be such a distinctive part of Magdalen’s community of wealthy white English gentlemen?

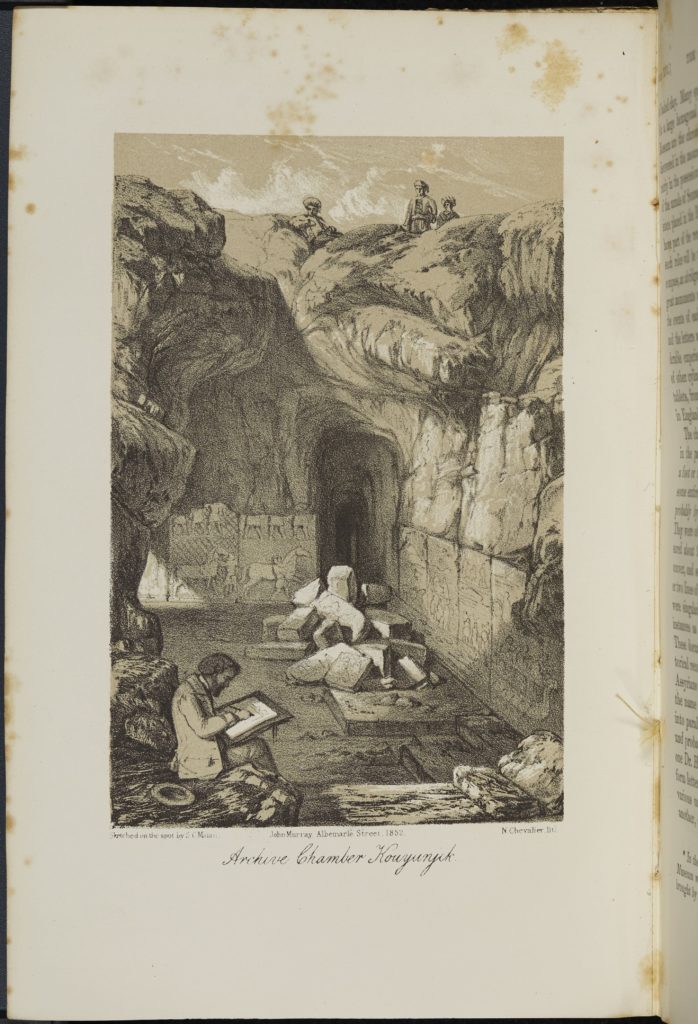

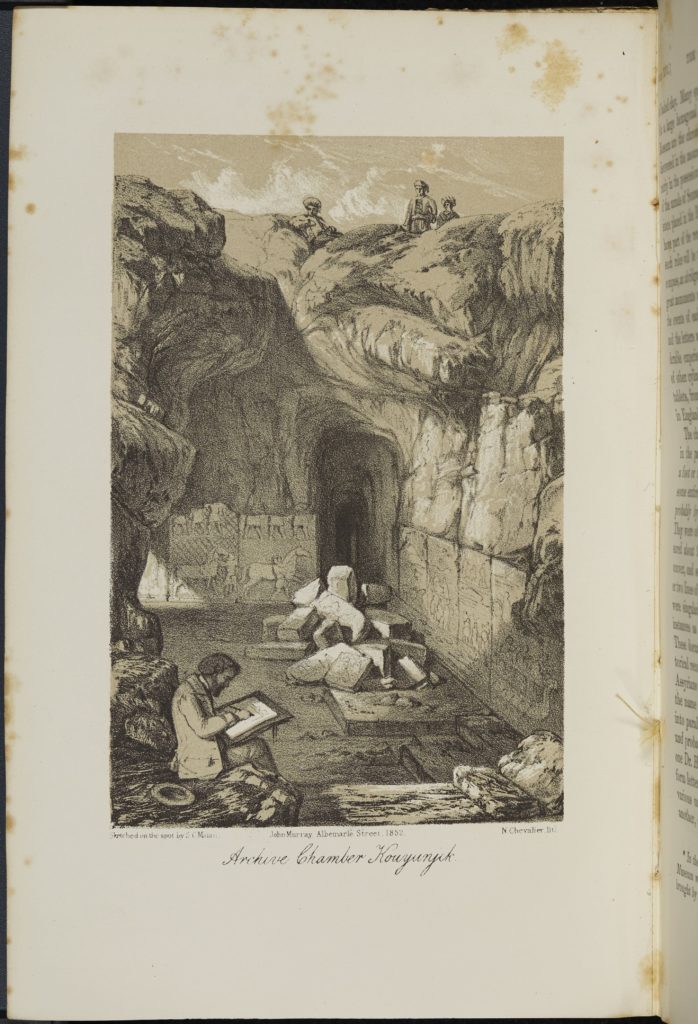

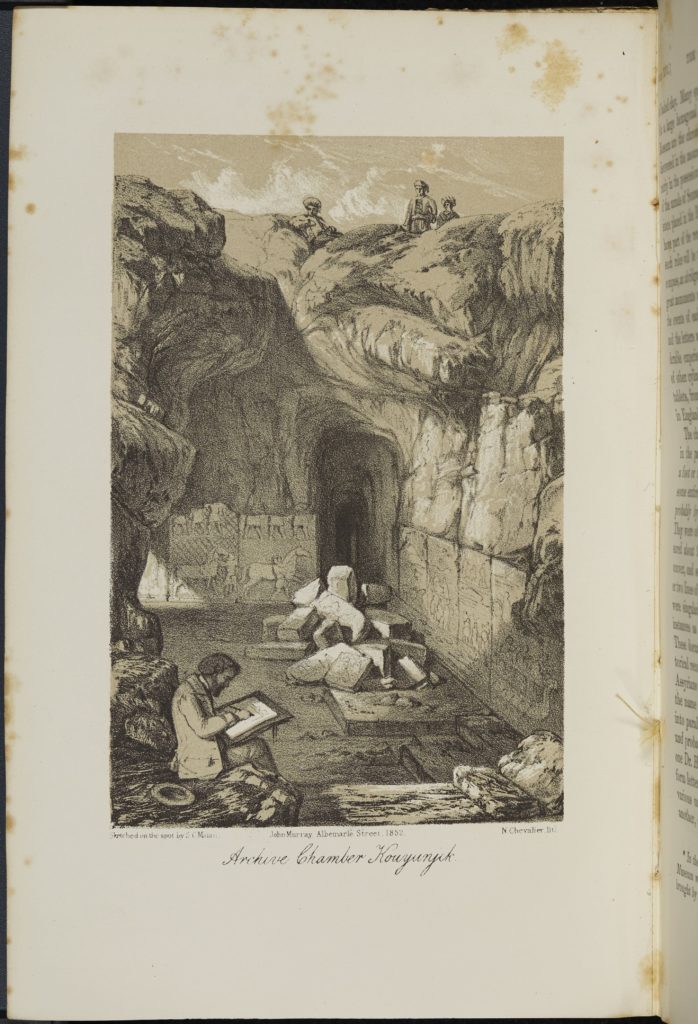

Austen Henry Layard, Discoveries in the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon: with travels in Armenia, Kurdistan and the desert, being the result of a second expedition undertaken for the Trustees of the British Museum (London: John Murray, 1853)

While Hormuzd Rassam was studying at Magdalen, Austen Henry Layard’s books about their first excavation were best-sellers. Having cut short Rassam’s studies, Layard employed him again on the second expedition to excavate the Assyrian palace at Nineveh, depicted in this illustrated volume from 1853. Rassam was crucial to the success of painstaking archaeological work, at a time when English exploration was competing with French ventures. In this way he was typical of many ‘imperial intermediaries’ whose skills and knowledge were critical to increasing European colonial power across the world.[2]

Magdalen College Library

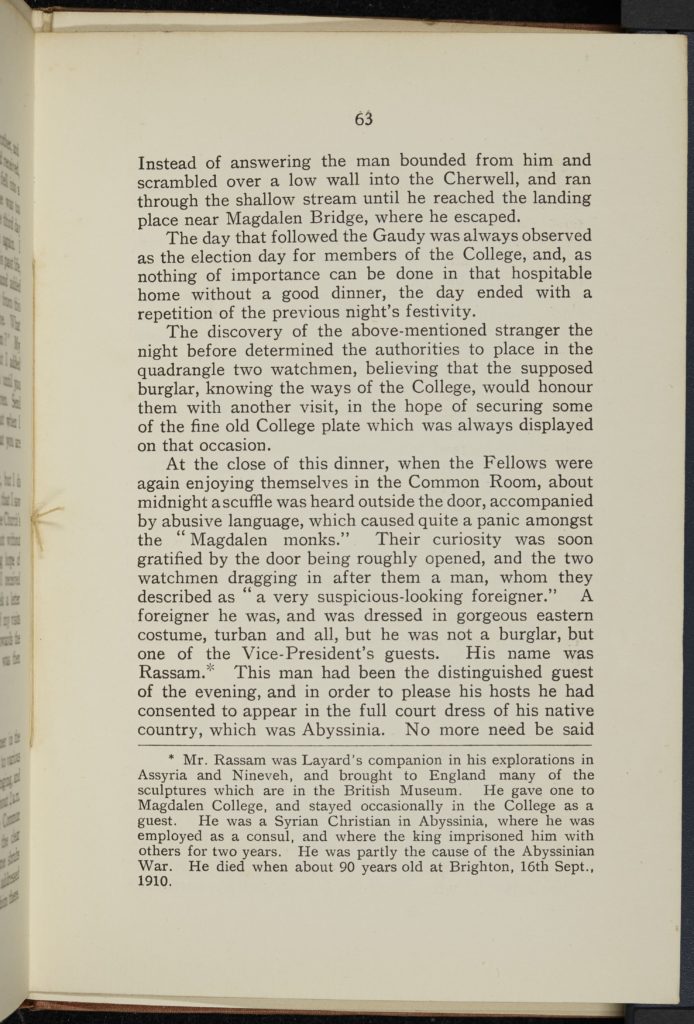

L. S. Tuckwell, Old Magdalen Days (Oxford: Blackwell, 1913)

Hormuzd Rassam was something of a celebrity at Magdalen. In 1854 he returned to Magdalen as a ‘distinguished guest’ at a Gaudy or feast.

This event reveals how people within the Magdalen community gave multiple meanings to Rassam’s heritage. Lewis Stacey Tuckwell was a boy chorister at Magdalen in 1854, but he remembered the evening sixty years later in his memoirs. Tuckwell wrongly describes Rassam’s country of origin as Abyssinia, now Ethiopia. Utterly different nations were flattened into a single ‘exotic’ ‘Other’.

Tuckwell described how Rassam again ‘consented to appear in the full court dress of his native country’. The language implies that it was not Rassam’s choice to stand out from the other guests, decked out in English evening dress. This account also provides a troubling insight into the everyday racial harassment that Hormuzd Rassam experienced. While attending the dinner, he was racially profiled as ‘a very suspicious looking foreigner’ and thrown out by watchmen, who were rewarded ‘for the blunder which had contributed so much to the amusement of the evening’.

Magdalen College Library

he claims direct descent from the ancient Assyrians, and says his nation has never been allowed to marry strangers, except just now, when his brother has married an English woman. Dr. Bloxam has spread it abroad that he is forty-fourth cousin of Nebuchadnezzar, and Rassam complains that he has been asked everywhere if it is really true… Mrs Routh laments his approaching departure: “We shall go into mourning when he is gone! Oh, he is such a good man, such a very good man, I am so fond of him”

Letter from J. B. Mozley to Maria Mozley, 11 June 1849, in J. B. Mozley, Letters of the Rev. J. B. Mozley, D.D., edited by his sister (London: Rivingtons, 1885), p. 200

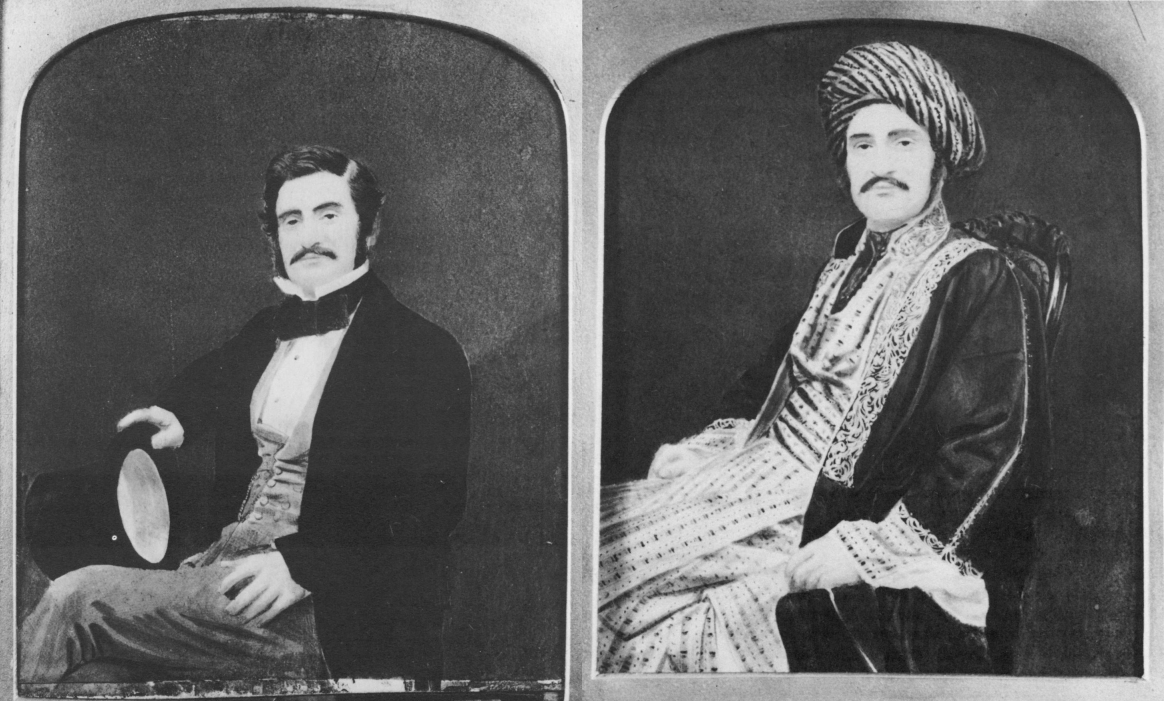

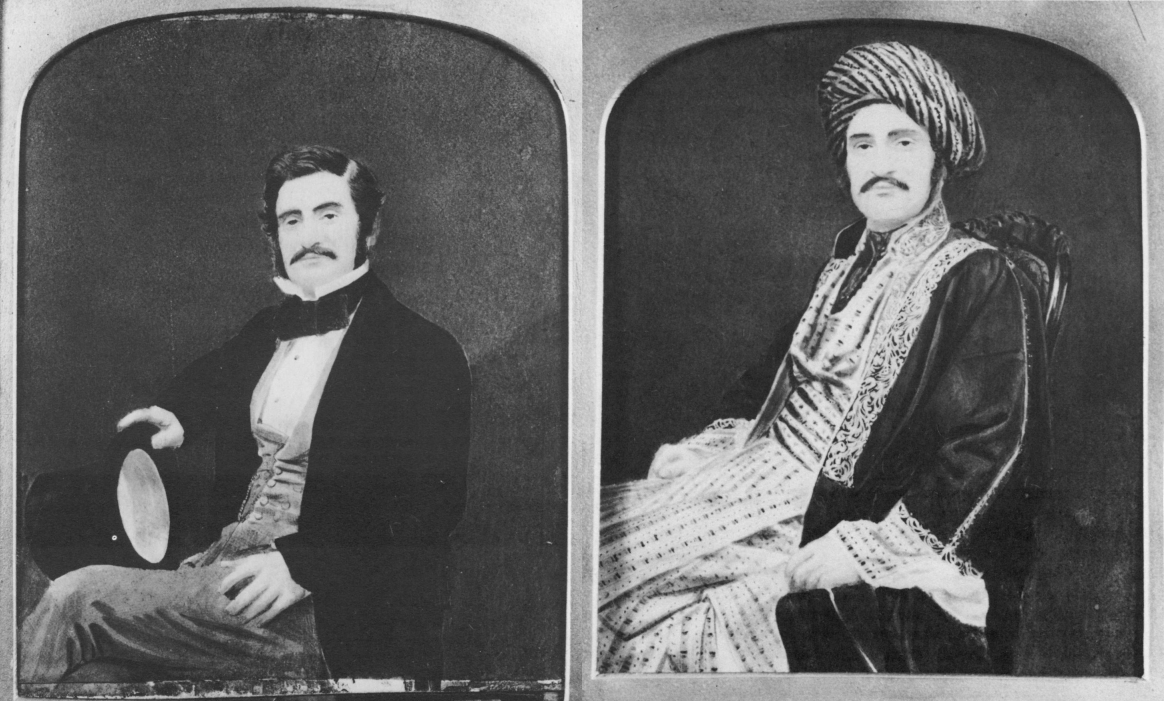

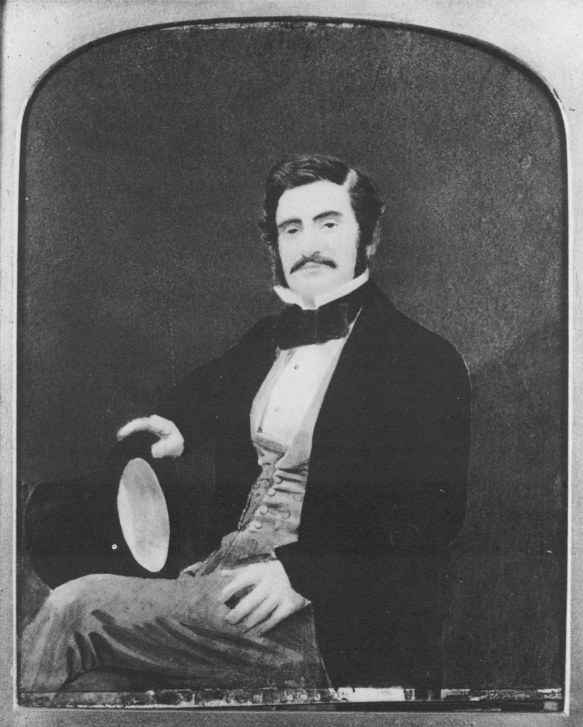

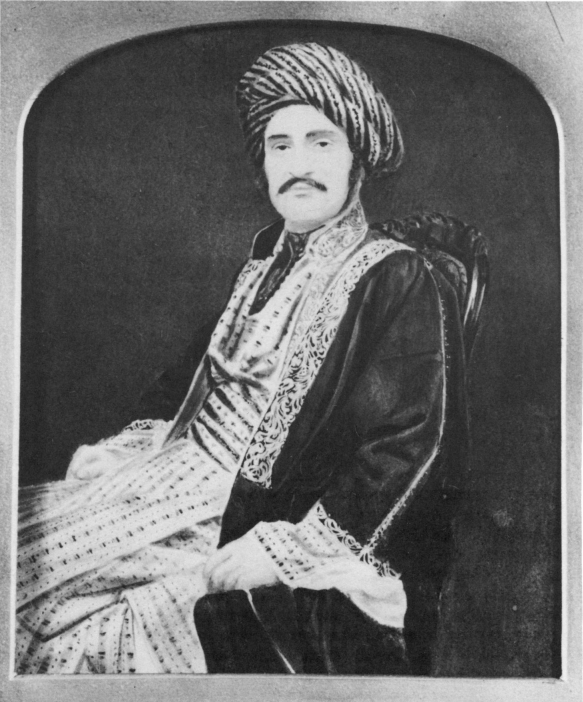

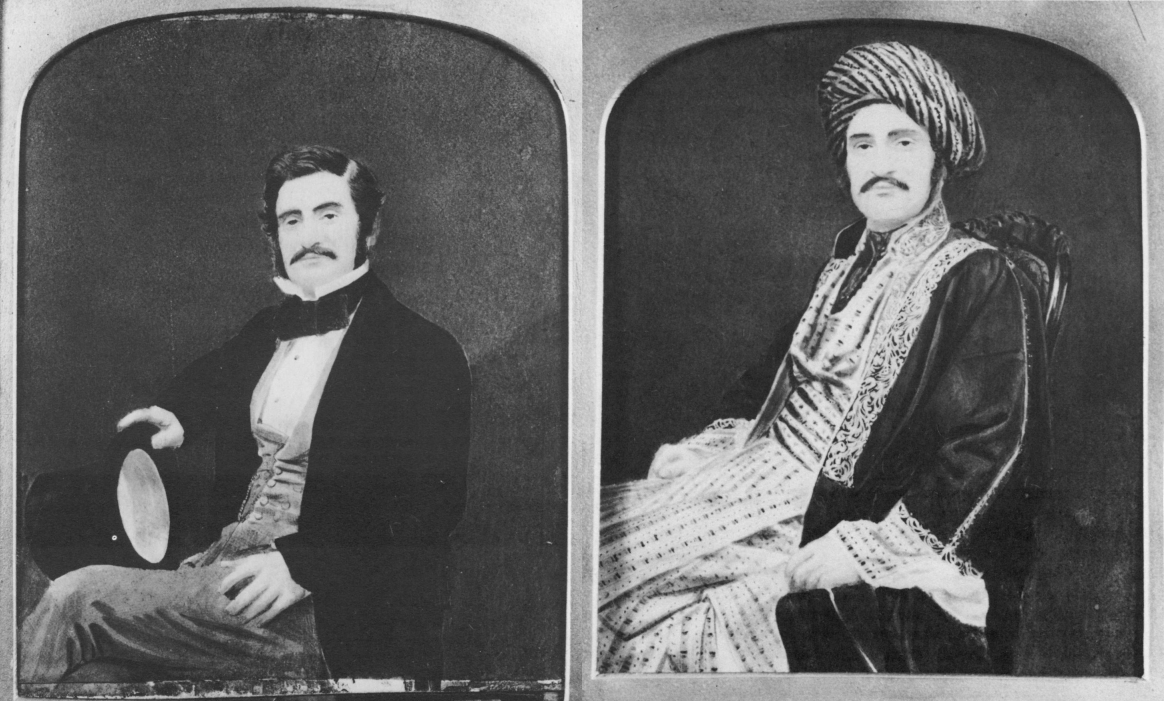

F. C. Cooper, Dual portraits of Hormuzd Rassam in ‘Western Dress’ and ‘Ottoman Dress’, 1851

Hormuzd Rassam’s dual identity intrigued people in mid-Victorian England. He sat for this pair of portraits soon after he had finished his studies at Magdalen. The images are an intriguing twist on a long Western tradition of dressing up in foreign dress for portraits.

While at Magdalen, he was frequently asked to wear ‘Chaldean costume’, a term used to describe the traditional dress of Assyrian people. One Magdalen fellow described in 1848 how Rassam’s tutor ‘has a Chaldean visiting him here, quite a young man, and I should think quite a beau in his own country. He wears ordinarily our common dress, but will put on his Asiatic one if you want him. He dined with us in Hall yesterday in it, and really looked exceedingly handsome’.[3] A later letter described another dinner in College, hosted by Eliza Routh, the wife of the President, where Rassam wore ‘full Chaldean costume, at Mrs Routh’s particular desire’.[4]

Despite later condemning ‘Oriental’ costume, in the 1840s and 1850s Rassam appears to have tolerated persistent requests to dress up as an ‘exotic’ curiosity to entertain his hosts.

Private collection. Reproduced with permission of the owner, Cornelius Cavendish. Images reproduced from Julian Reade, ‘Hormuzd Rassam and His Discoveries’, Iraq, 55 (1993): 39-62

Assyrian relief from Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud, Iraq, c. 883-859 BC, excavated during Austen Henry Layard’s first expedition, 1845-7

Rassam presented this relief to Magdalen on his departure from College in 1849, as a token of ‘sincere thanks for the kindness I have received from you first, and also for the indulgence with which the college generally has treated me’.[5] Rassam had a close relationship with President Martin Routh and his wife, Eliza, and valued his time at Magdalen.

The relief features a winged genie and prayer, intended as spiritual protection for the inhabitants of the palace that Rassam had helped to uncover.

Magdalen College

Assyrian relief fragment from Nimrud, Iraq, c. 883-859 BC

These fragments of an Assyrian relief were unearthed at Nimrud, Iraq in 1850. It is thought that Rassam donated them on his visit to England in 1851, probably as a gift to John Rouse Bloxam, a fellow and clergyman at Magdalen.

Nimrud was home to multiple Assyrian palaces decorated with carved gypsum reliefs, a form of local marble. Relief panels that lined their walls are in many museums around the world, including the British Museum.

Magdalen College

To Mr. Hormuzd Rassam, who usually accompanied me in my journeys, were confided, as before, the general superintendence of the operations, the payment of the workmen, the settlement of disputes, and various other offices, which only one, as well acquainted as himself with the Arabs and men of various sects employed in the works, and exercising so much personal influence amongst them, could undertake. To his unwearied exertions, and his faithful and punctual discharge of all the duties imposed upon him, to his inexhaustible good humour, combined with necessary firmness, to his complete knowledge of the Arab character, and the attachment with which the wildest of those with whom we were brought in contact regarded him, the Trustees of the British Museum owe not only much of the success of these researches, but the economy with which I was enabled to carry them through. Without him it would have been impossible to accomplish half what has been done with the means placed at my disposal.

Austen Henry Layard, Discoveries in the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon: with travels in Armenia, Kurdistan and the desert, being the result of a second expedition undertaken for the Trustees of the British Museum (London: John Murray, 1853), p. 101

![Hand written letter with printed address ’30 Westbourne Villas, Hove, Brighton. The letter reads: 12th July 1910. To the librarian of Magdalen College Oxford. Dear Sir, I am told by my daughter [unclear] that there is no name of the presenter of the sculpture which I had presented to that institution in 1849. That sculpture, with many others were found in the [artificial?] [unclear] called “Nimrud” the ancient site of Calah of the Bible-, in Genesis 10th chapter 11th verse. I am dear Sir, yours faithfully, H. Rassam.](https://marginalisedhistories.magd.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/F23.C5.15-630x1024.jpg)

![Hand written letter with printed address ’30 Westbourne Villas, Hove, Brighton. The letter reads: 12th July 1910. To the librarian of Magdalen College Oxford. Dear Sir, I am told by my daughter [unclear] that there is no name of the presenter of the sculpture which I had presented to that institution in 1849. That sculpture, with many others were found in the [artificial?] [unclear] called “Nimrud” the ancient site of Calah of the Bible-, in Genesis 10th chapter 11th verse. I am dear Sir, yours faithfully, H. Rassam.](https://marginalisedhistories.magd.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/F23.C5.15-630x1024.jpg)

Hormuzd Rassam letter to the Magdalen College Librarian, H. A. Wilson, 12 July 1910

After leaving Magdalen, Hormuzd Rassam developed a career as a diplomat in the Indian Office and conducted further important excavations in Assyria on behalf of the British Museum. Yet his legacy was tarnished by unfounded attacks on his integrity in the 1890s, and a consistent racist refusal by the British Museum to recognise his accomplishments as an archaeologist.

After the death of President Routh in 1854, Magdalen, too, seemed to forget about its debt to this extraordinary alumnus. In this letter, penned just weeks before his death in 1910, Rassam wrote to the College Librarian to enquire why ‘there is no name of the presenter of the sculpture that I had presented to that institution in 1849’. It seems that this request for recognition was ignored. No attribution for the outstanding relief was given for over a century.

MCA: F23/C5/15

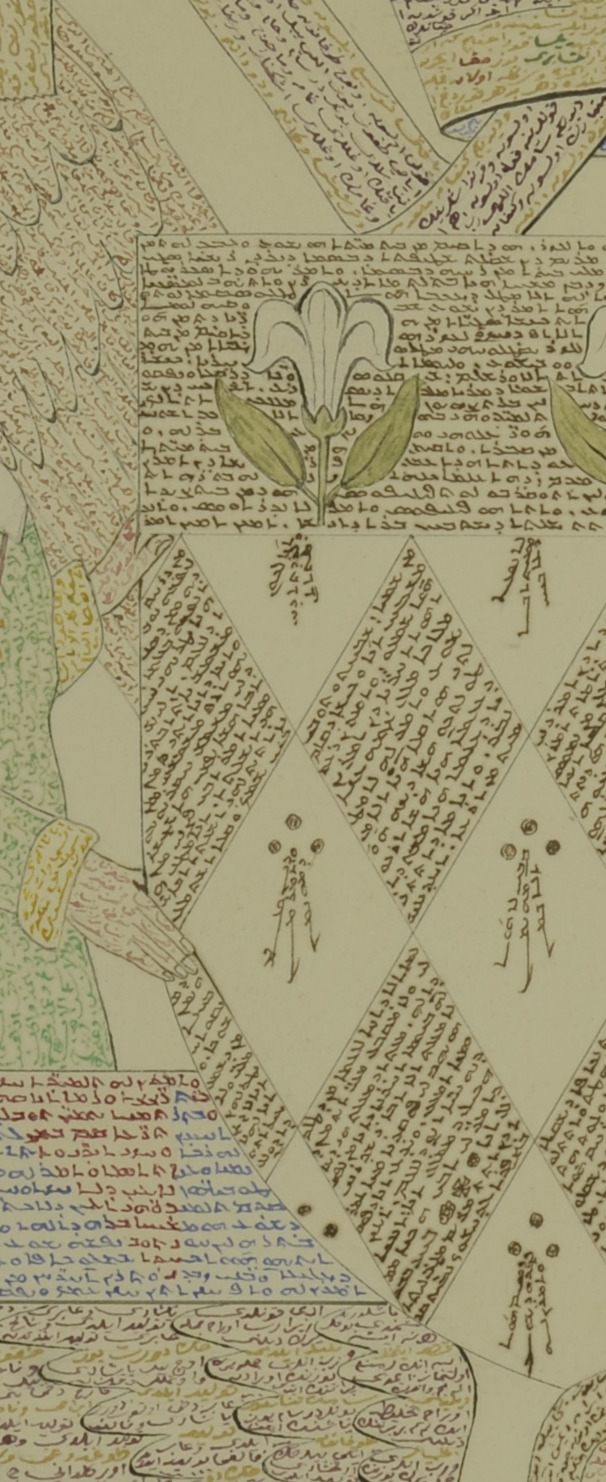

Magdalen College Arms drawn by Hormuzd Rassam, c. 1849

This unique artwork represents Hormuzd Rassam’s hybrid identity and Christian faith. In the centre, Rassam placed the Magdalen College Arms, surrounded by three angels, with the College founder, William Waynflete’s, bishop’s mitre on top. Each of the panels of colour is composed of a chapter from the Old and New Testament written in Arabic, Chaldean, and Turkish. Another version of this coat of arms is on the ceiling in Cloisters, near the stairs to the Old Library.

Rassam donated this work of art, drawn in coloured inks with gold leaf embellishment, on his departure from Magdalen in 1849. A similar piece was donated to the Bodleian Library ‘as a mark of thanks for the manner in which he had been received’. Despite the tiny calligraphy, Rassam reported that the art ‘occupied only forty-eight hours in execution’.[6]

In his letter of thanks to President Routh, Rassam referred to England as both ‘this happy land’ and ‘this blessed land (my adopted country)’.[7] He increasingly identified as an Englishman over the course of his life, before becoming a naturalised citizen in 1870, but experienced persistent difficulties in being accepted as the true Englishman he felt himself to be.

MCA: A9/3

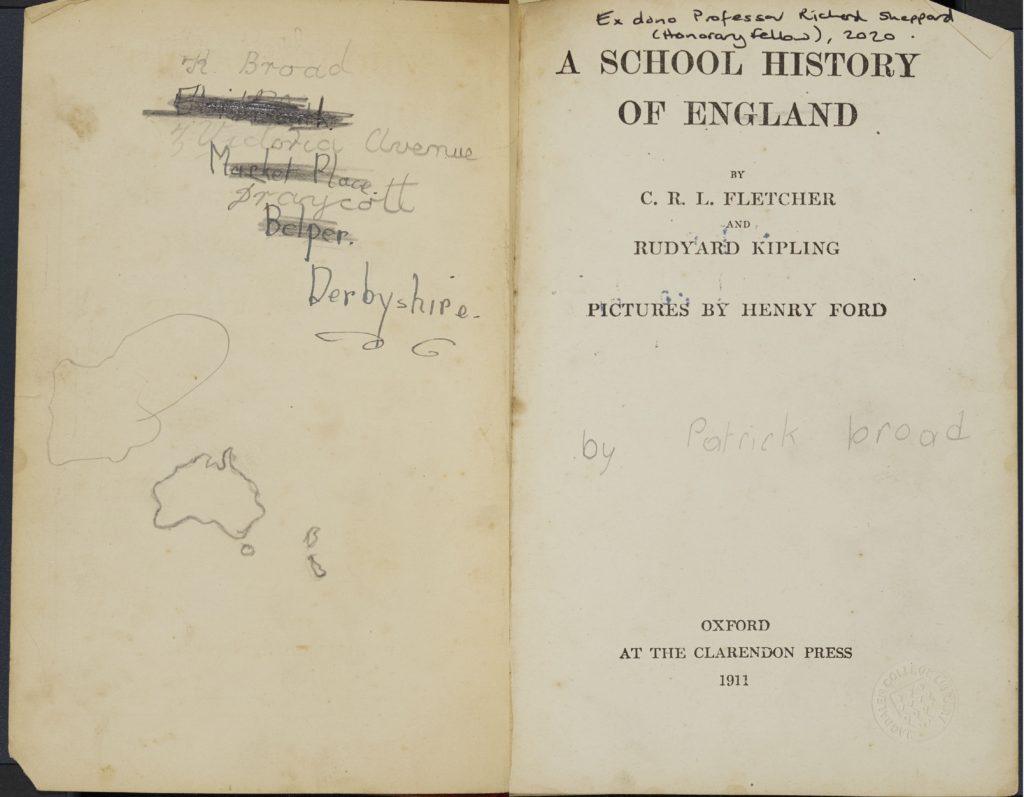

R. L. Fletcher and Rudyard Kipling, A school history of England (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1911)

We have not been able to identify any other students of colour who studied at Magdalen before the First World War. Hundreds of men and, from the 1870s, women, who had been born across the British Empire, graduated from other colleges.

Magdalen welcomed many white Rhodes Scholars from across the globe from 1904, but in 1907 the college refused, on the grounds of race, to offer a place to the first African-American Rhodes Scholar, Alain Locke.[8] Magdalen undergraduates were also notorious for mocking students of colour who were admitted to other colleges.[9]

After resigning from his Magdalen fellowship, the historian Charles Fletcher collaborated with Rudyard Kipling to publish this volume in 1911. One reviewer condemned its racist stereotypes as ‘the most pernicious influence’, but even ‘nearly worthless’ books had the power to popularise national narratives of ‘Anglo-Saxon’ superiority and the imperial civilizing mission.[10] The History remained a best-seller for forty years, shaping the understanding of generations of children. Children’s annotations on this copy show several young readers engaging with the text.

Racist and imperialist visions such as Fletcher’s contrasted with the complex hybrid identity that Hormuzd Rassam had represented while studying at Magdalen sixty years earlier.

Magdalen College Library