Numbers of students of colour increased between 1970 and 2015, driven primarily by the admission of larger numbers of international postgraduate students with scholarships. By 1979 45 per cent of new graduates came from beyond the UK. Two years later, one student described how ‘Magdalen prides itself as being a college with a high intake of foreign students, and a cosmopolitan atmosphere’. From 1979, this community also included women, when the first 32 women were admitted to study at the previously all-male college.

The first of Magdalen’s eras of student activism occurred in the 1970s and 1980s. This contrasts with the sparse minutes of the Junior Common Room (JCR) between the 1930s and 1960s, which show no signs of engagement with global struggles for decolonisation or civil rights. The archive from the 1970s and 1980s reveals many more Magdalen students challenging conservative values within a community that one student described as a ‘male public school transferred to Oxford’.[17]

Some students who challenged racial inequalities and global hierarchies did so individually through their studies, but most of this political work was done in communities. These groups brought together students from across the University in radical and transnational activism. This means that the written record offers few clues as to who was involved with these collectives.

Between the mid-1990s and mid-2010s, student engagement in anti-racist and global activist movements returned to the archival shadows. Was the brief prominence of late-twentieth-century activism merely a product of an era of photocopiers and paper publications that made students’ perspectives uniquely visible and preserved? Or were these true changes in student culture and experience?

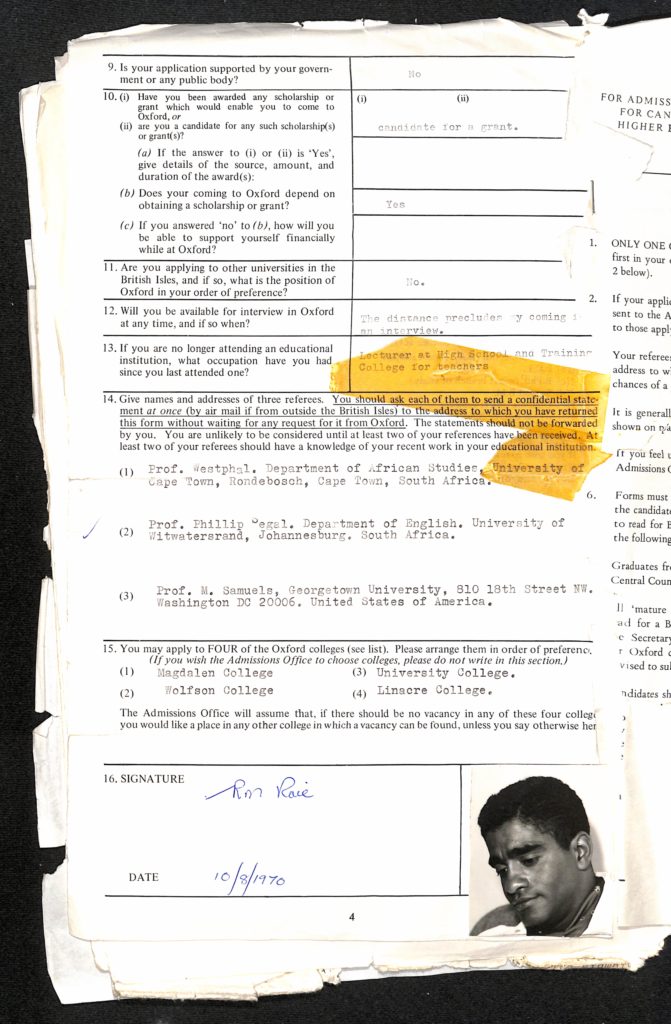

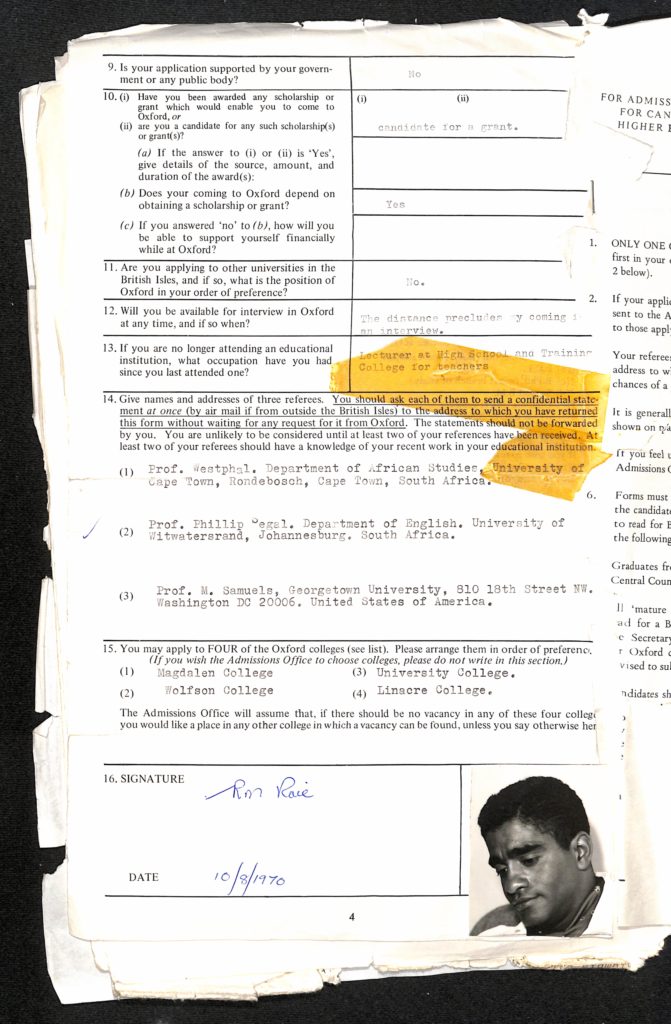

Richard Rive student file: letter requesting admission to Magdalen, 26 July 1970

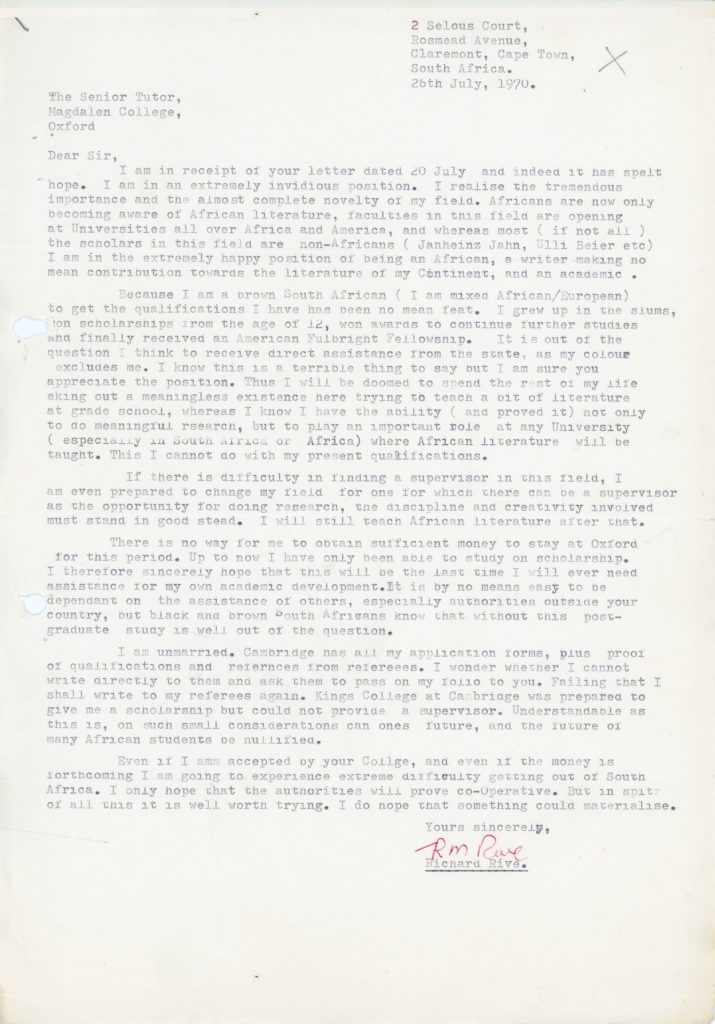

In 1971 Richard Rive, a South African novelist and anti-Apartheid activist, was admitted to Magdalen to study for a D.Phil (Ph.D.) in English literature.

The personal tone of 39-year-old Rive’s letter of application contrasts with the brief letters that many students submitted alongside their forms. Richard Rive’s letter was persuasive. He was awarded a College scholarship to Magdalen and subsequently received substantial additional funds to complete his research in South Africa, including a scholarship funded by the Junior Common Room (JCR).

Scholarships from Magdalen were transformative for Rive. Doctoral study was ‘well out of the question’ without financial assistance that the racist South African government denied to students of colour. On accepting his place at Magdalen, he wrote that he was ‘representing 14 million non-whites in this country of ours’ and thus ‘cannot but do my very best.’[18]

MCA: AD/74

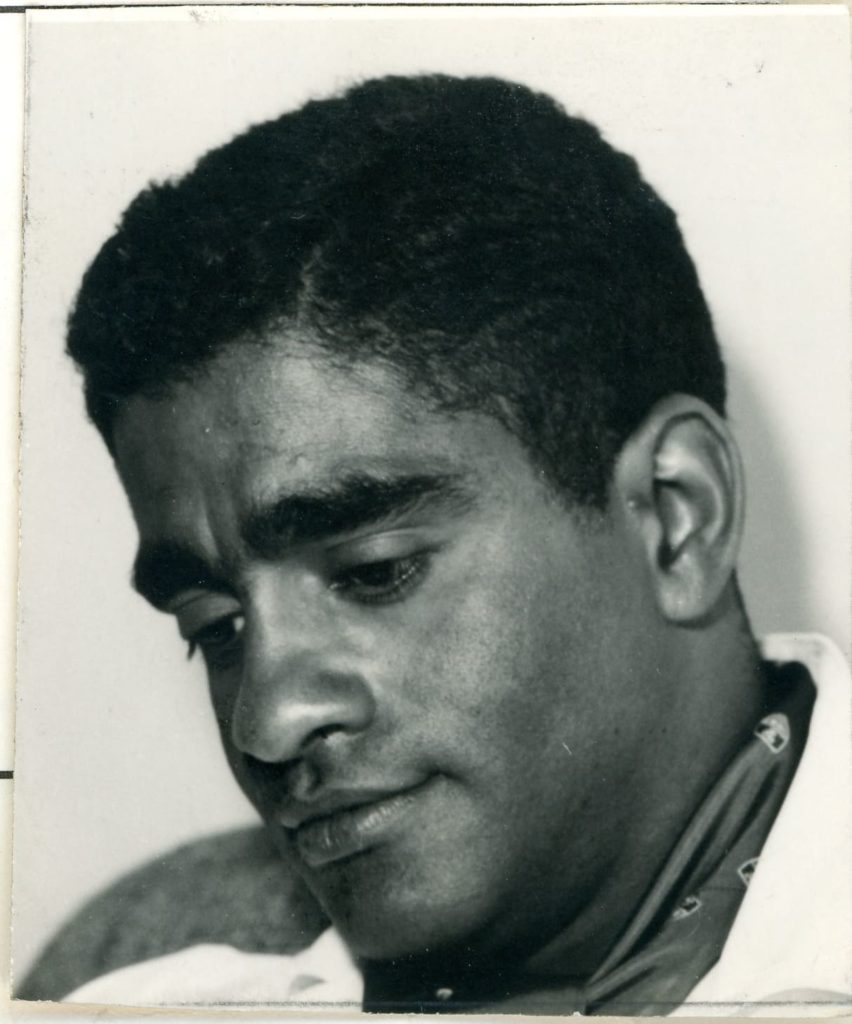

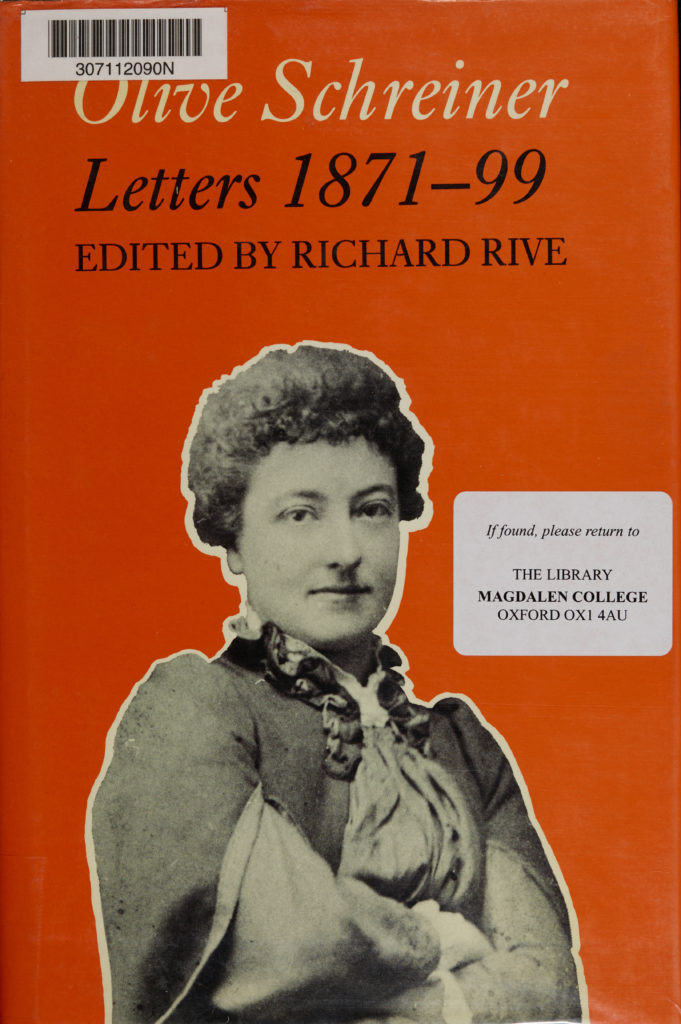

Richard Rive, Olive Schreiner. Letters, 1871-99 (Cape Town: David Philip, 1987)

Richard Rive’s innovative application to research ‘African literature’ was obstructed by academic barriers, as well as financial and racial ones. He had been denied a place at Cambridge because there was not a supervisor willing to supervise in this field.

Rive went on to research the pioneering feminist and South African novelist, Olive Schreiner, and he later published this edited collection of her letters. Rive remained profoundly grateful for Magdalen’s graduate scholarship, which enabled his career as an academic and path-breaking writer. When he died in 1989, he left his personal library to Magdalen, including around 200 first-edition and autographed books by him and his fellow writers. The seminar room in the Longwall Library is now named after him.

Magdalen College Library

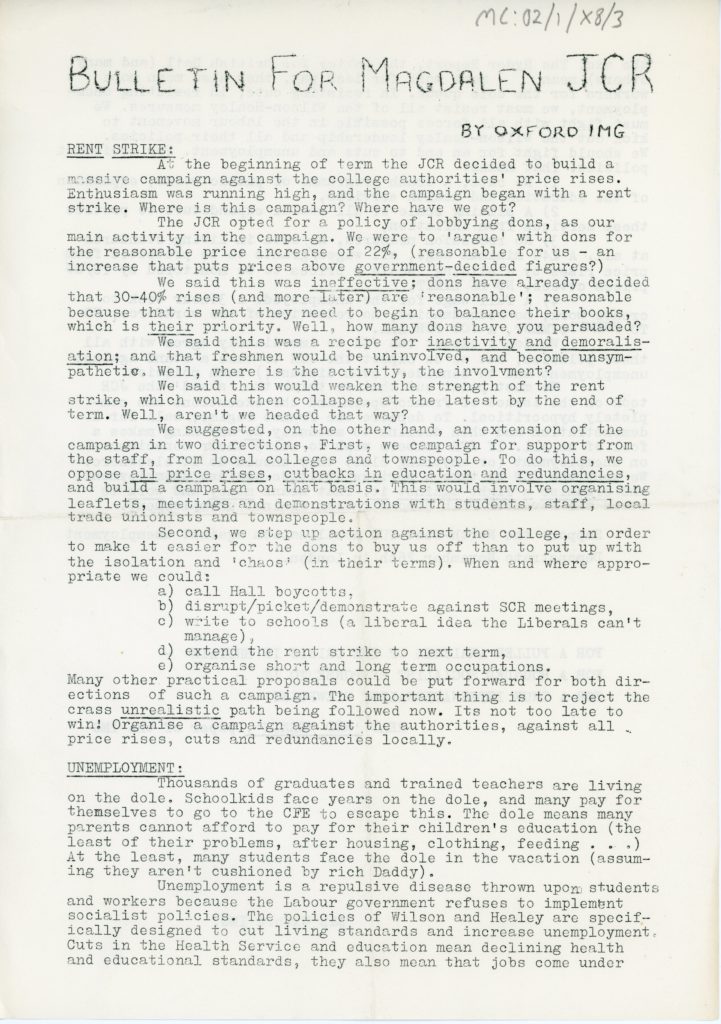

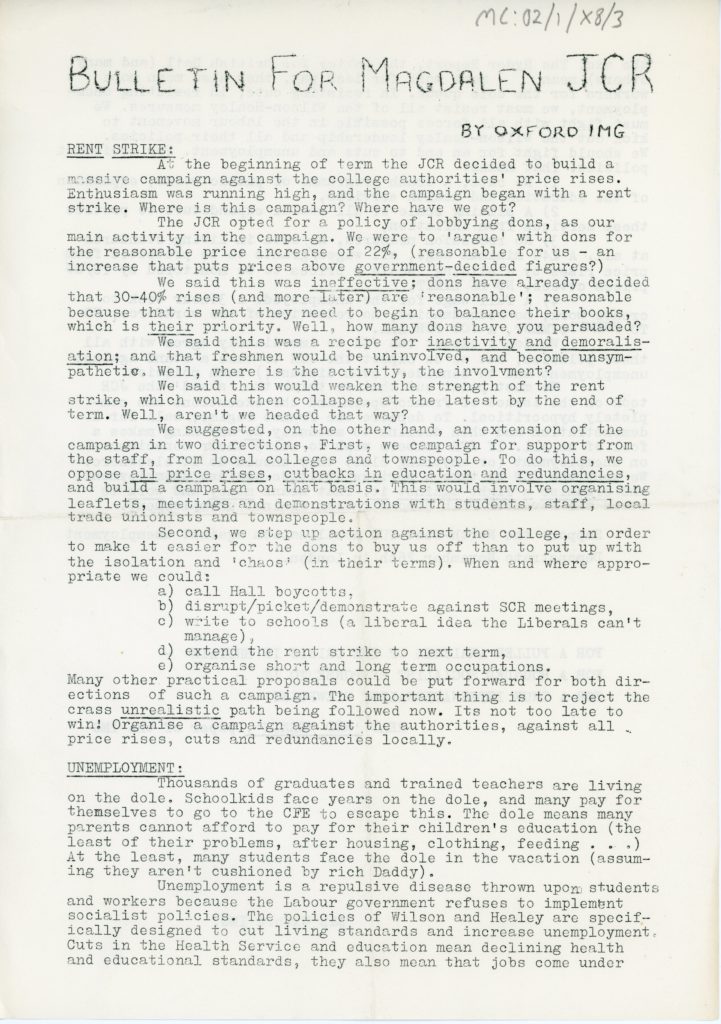

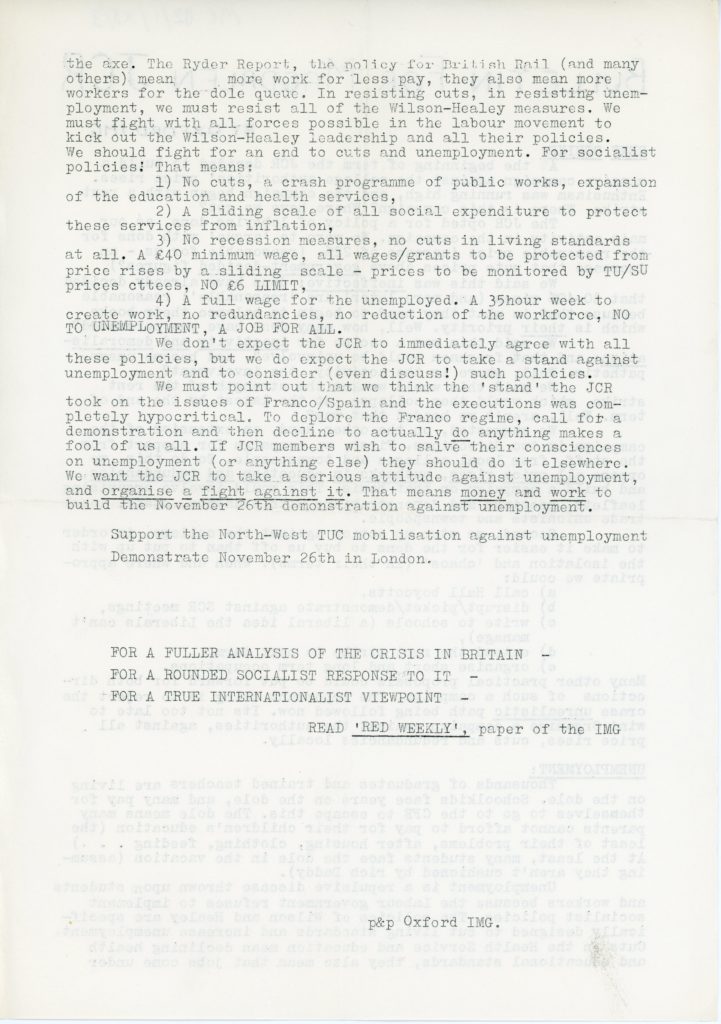

Oxford IMG, ‘Bulletin for Magdalen JCR: Rent Strike’, 1975

The Magdalen undergraduate body, the Junior Common Room (JCR), was at its most politicised in the 1970s. Minutes and publications reveal frequent debates between College’s ‘Left Caucus’ and ‘Right Caucus’, small groups of students with contrasting perspectives on political issues.

The International Marxist Group (IMG) sought to link radical transnational activism to local social change. Following a university-wide rent strike in 1975, the IMG worked to counter ‘a traditional hostility between working class staff and upper class students’, proposing activism against staff redundancies and wage cuts. The IMG and ‘Magdalen Left Caucus’ also argued for staff representation within College decision-making. In an era of strikes and unemployment, including within an increasingly ethnically diverse city, some students sought solidarity across class lines.

A member of the ‘Right Caucus’ condemned the anti-racist activism of the IMG in a 1976 JCR Newsletter, arguing instead for global white racial solidarity: ‘White Rhodesians are our own flesh and blood, and to abandon them while they are still officially part of the British Commonwealth is tantamount to genocidal irresponsibility’.[19] The College archive does not reveal the impact of these heated debates.

MCA: O2/1/X8/3

‘An IMG Comrade’, ‘Subverts, Perverts & Extroverts: A Brief Pull-Out Guide’, The Oxford Strumpet, 10 October 1975

Anti-racist activism was central to the work of the ‘International Marxist Group’ in the 1970s. The Group described itself as ‘the British section of the Fourth International, founded by Leon Trotsky in 1939’. They had an explicitly anti-colonial, anti-racist, and transnational philosophy: ‘We believe that the fight for socialism necessitates the abolition of all forms of oppression, class, racial, sexual and imperialist, and the construction of socialism on a world wide scale’.

As this extract illustrates, The Oxford Strumpet promoted a wide range of leftist and progressive student movements. The publication appears to have been archived at Magdalen while it was edited from within the college, but its contributors and readers stretched across Oxford.

MCA: O2/1/N6/1

Anne M. Sebba, ‘The First Ladies… in Washington and at Oxford. The “pretty average” Rhodes Scholar’, newspaper clipping, 26 September 1979

Karen Stevenson was the first Black American woman Rhodes Scholar. She was also in the first cohort of women admitted to Magdalen in 1979. Stevenson had been a pioneer throughout an outstanding academic and sporting career, as this newspaper interview reveals.

MCA: F54/2/MS8/2

Interview with Karen Stevenson, Magdalen College, 2019

When reflecting forty years later on her experience at Oxford, Stevenson explained that ‘being a Black woman was much harder than just being a woman, for sure’. She described how the ‘racial attitudes’ of ‘other students and around town’ meant that Oxford could be ‘a very challenging place’. Stevenson recalled an ‘outstanding’ academic experience of studying history because ‘my dons were always professional, courteous, encouraging, and I gained a kind of confidence working with my dons at Magdalen’.

You can find out more about Karen Stevenson’s experiences of studying at Oxford by listening to extracts from her oral history interview below.

On her experiences as part of the first cohort of women students at Magdalen:

On her experiences specifically as a Black woman:

I don’t think you know immediately how it changes you. You see over time how the breadth and intensity and adventure, or challenge, of the experience of being at Oxford works through you and informs how you are in the world.

MCA: OH4_I0013 karen stevenson

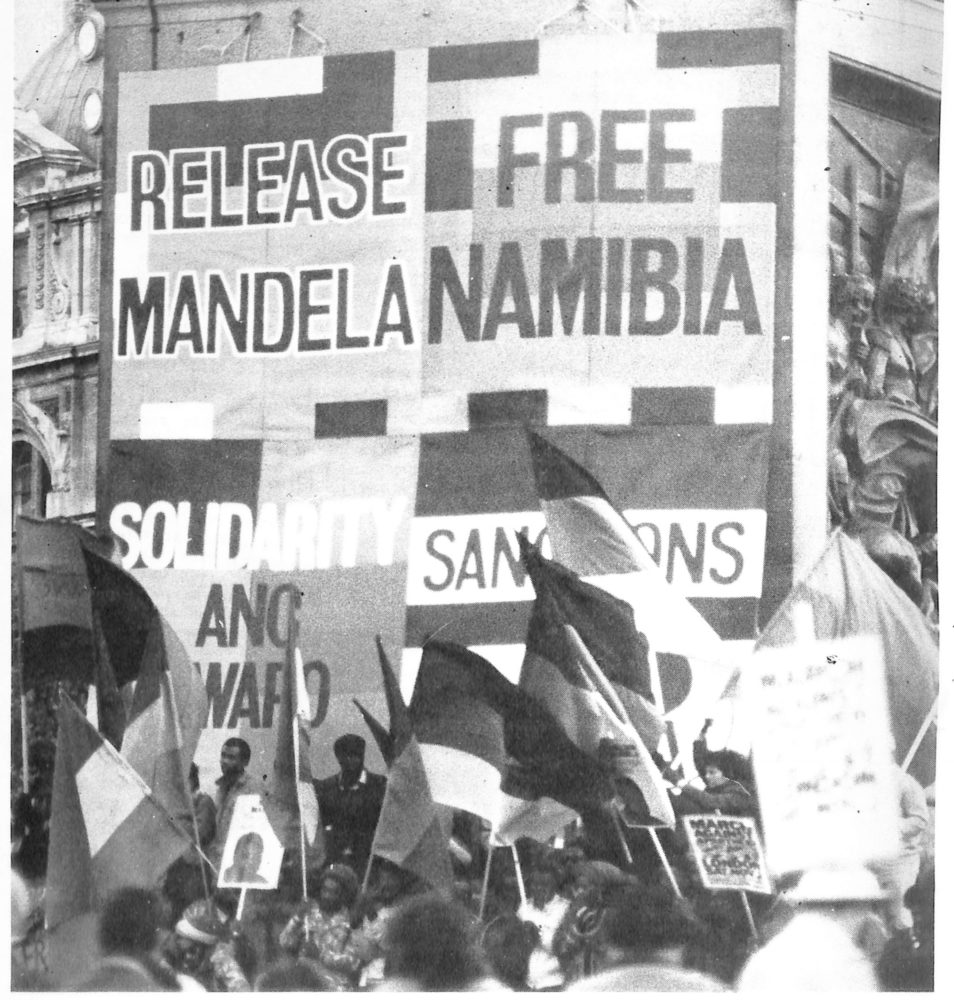

‘This JCR proposes to support the Namibian struggle for literacy and solidarity….’, The Stag, Hilary 1987

Featured in the header image of this webpage. Photo credit for the image within this article, taken at an anti-apartheid demonstration in London: Antonia Bunnin (PPE, 1985).

The rich archive of Junior Common Room (JCR) publications from the 1980s reveals how students engaged with international anti-racist movements. This article reported on the JCR’s work to raise awareness of Namibia’s struggle for independence from Apartheid South Africa, not achieved until 1990. In discussing these efforts, students combined ideas of global solidarity with the language of humanitarianism.

The most sustained student fund-raising was for Magdalen’s ‘Third World Scholarships’, established in the late-1950s. Across these decades, there were references to Magdalen as a College that ‘prides itself on the promotion of Third World Scholarships’.[20] Scholars were selected based on financial need and social commitment, prioritising ‘those whose work is likely to assist the community on return to their countries.’

Reza Moghadam, a mathematics student who became Magdalen JCR president in 1984, published a powerful article reflecting on the ‘Third World Scholarships’. He interviewed the current scholar who reported that the first question he had been asked on arrival at Oxford was, ‘Do you come from a primitive tribe?’. Moghadam concluded his article by questioning racial inequalities within the UK, noting that the scholar ‘provides a very positive element in Oxford life and culture and people consider it romantic to have him here: do they feel the same way about a black man from Birmingham?’[21]

MCA: O2/1/N3/15

Beth Okamura

Group photograph of some Magdalen College fellows, 1989

Beth Okamura, a biologist who researches ecology and evolution, was appointed to a tutorial fellowship at Magdalen in 1988. She was only the second woman to be appointed to a permanent fellowship at Magdalen. In this picture, she is seated on the front row, second from the right.

MCA: B/3/27

Interview with Beth Okamura, Magdalen College, 2021

Okamura grew up with a ‘mixed racial background’ in rural California. When interviewed, she explained that

I’ve never felt that being female is the thing that intimidates me, it’s feeling that racially I’m not going to be accepted and I’m going to… stand out, and be the subject of racial attacks.

When reflecting on her time at Magdalen, however, she recalled that

I didn’t feel intimidated at my racial background in being put into the middle of Magdalen College because it wasn’t in the US… it was a different culture, so I didn’t feel that that was going to be something that was an issue.

She felt ‘comfortable’ at Magdalen, an experience that she described as ‘fantastic fun and a really great place to be for some years’.

Today Beth Okamura is a Merit Researcher at the Natural History Museum.

You can hear more about Okamura’s experiences at Magdalen below.

On arriving at Magdalen:

On her experiences as a fellow at Magdalen with a ‘mixed racial background’:

MCA: Acc2022/25

Henry Bonsu, ‘Being Black’, Magdalen College Freshers’ handbook, 1990

Kiran Khetia, ‘ethnic minorities’, JCR Freshers’ Handbook, 1995

Junior Common Room (JCR) freshers’ handbooks provided new students with a guide to life at Magdalen. By 1990 these included a short piece by a student of colour, including the examples displayed here.

Students presented a positive image of College in the 1990s, often emphasising the contrast between their expectations that ‘they might not quite fit in’ and their experiences.[22] In 1997, one student wrote ‘in truth there is really very little to say about this subject’.[23] These were public documents and much may have been unsaid. Yet, when recalling this period almost thirty years later, one international undergraduate student remembered an ‘enriching and positive’ experience in a ‘reasonably cosmopolitan community’.[24]

This interview allows you to find out more about the experiences of one of the student writers, Henry Bonsu, who came to Magdalen in 1986 to study Modern Languages.

MCA: O2/1/N9/2; O2/1/N9/7